Depression is a truly vicious bastard. It’s hard to capture or explain just how debilitating and awful it is, unless you’ve lived with it, or lived with someone you hold dear and close to you who suffers at its hands. It’s also a crushingly heavy topic, so it’s little wonder few games attempt to tackle it, and why those that do are often indie games that are free from the need to be widely accessible for the sake of maximising profit. It’s an illness that has become increasingly visible in the mainstream though, as newer generations break free from the stoic silence and emotional unavailability that typifies the mid-20th century generations, and I think that it’s more important than ever to have pieces of art that try and address it – and, perhaps more to the point, to share those pieces of art.

Content warning: Depictions and discussion of depression, anxiety.

You Used To Be Someone (PC)

Released: Dec 2017 | Developed / Published: Squinky

Genre: Interactive narrative | HLTB: 30 mins

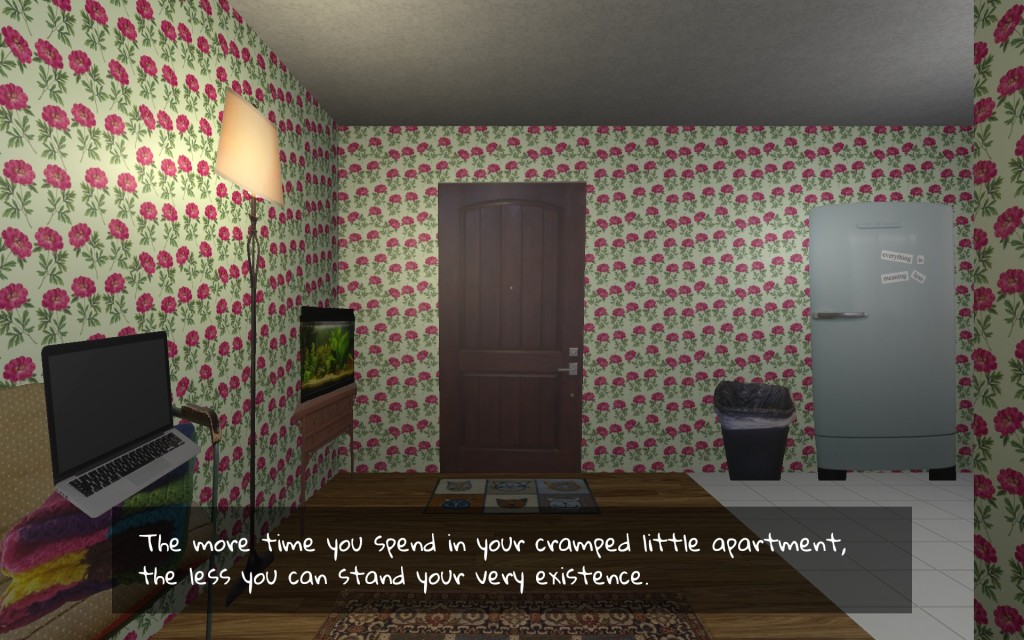

The most striking thing about You Used To Be Someone initially is the way it looks. The game begins with your character in their apartment, staring at the hideous flowery wallpaper that stretches in an unbroken pattern over the entire wallspace. It’s mind-numbing, like if those exciting liminal spaces you see crop up in internet creepypasta like “The Backrooms” were somehow made even worse. In short, it’s perfect – an absolute encapsulation of just how hateful and oppressive even something as benign as the walls of your own home can feel at your lowest. Because you start in a nook, there’s a tiny bit of the wall that protrudes closely into your field of vision, creating a corner that blocks your view of the entire apartment. The effect is profoundly claustrophobic, making you feel as if you’re in an impossibly tiny, enclosed space.

The scene before you is sparsely furnished: a laptop perched on the side, a lamp casting a sickly weak orange glow, a crooked bin, a lonely fishtank. All the furnishings are represented with flat 2D images, giving an almost chaotic collage feel to the game’s aesthetic. While it was an initially odd feeling to see, and not a little bit disorientating, the more I played the more the style grew on me. It feels appropriate for everything to feel flat, weird, hollow.

The goal of the game is to get out of your apartment. It’s not particularly hard to, in ludic terms – you go to the door, flick through the dialogue and hit the option to get outside. That’s not the end of the game – there’s actually plenty more – but when I say that that’s the goal I mean that it’s the thing our protagonist needs to do. After all, when you’re depressed it’s always hammered home by the well-meaning that isolating yourself from the world and not getting any exercise at all is only going to compound your mood. I’ve been on both sides of that chat. It rarely helps either participant, even if it’s true.

Stepping out into the street beyond your front door does little to help the feelings of claustrophobia. The buildings tower above you in harsh straight lines, looming far overhead, and bright signs and clashing sounds vie constantly for your undivided attention. There’s a real eerie uneasiness about the visuals; the flat, boxed-in streets give the impression of having been dropped into a playset – it’s all so artificial.

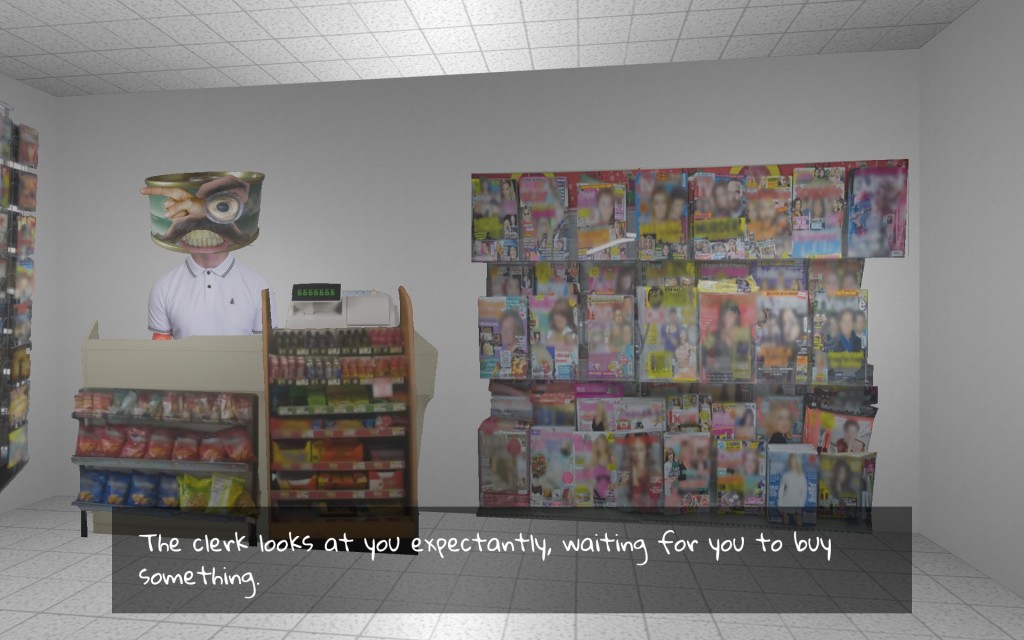

Stepping into some of the open shops feels like a window into a deranged mind. The cafe has mismatched art sprayed haphazardly across the walls, and the general store’s cabinets are off-shape and every product blurs together into one hazy mush. The walls of the fast-food restaurant are untextured coloured stripes rather than the textures everywhere else in the game making it the most unsettling and alien location, and when you visit a small bar the effect of all the aesthetics, with all the chairs and tables flat to the wall, creates a potent sense of being vulnerable and stuck in the open, leaving you floundering as you try and find a space where you don’t feel like you’re the centre of attention.

And the people! Dear Lord, the people. These are the most abstract and horrifying depictions in the game. Almost all of them are highly stylised, with cut-out eyes and wide mouths fixed in rictus grins; they look like a note left by a serial killer. It’s a startlingly effective depiction of the disconnect that can come with major depressive episodes, as people are reduced to job roles and blank expressions. Further in the town there’s a club which our protagonist timidly ventures into, only to find the crowd a mess of blank faces and knit together in a tight, impenetrable crowd, forcing us to wander the periphery. Like the rest of the places in the game, there’s nothing to do but wander, listen to your internal narration as it gives voice to your own self-hatred, then get bored and leave.

There’s no ending to the game, or at least, none that I found, save for finally exhausting your social options and returning to your apartment. Like the rest of the game, it’s a frighteningly accurate rendition of the entire depression experience. I don’t think I’ve played a game that felt so unrelentingly resonant, to be honest. I wouldn’t say I liked it, per se, but as an insight into the author’s mind and as a means to communicate what some of the feelings of depression are like, You Used To Be Someone fulfils its brief with a frank brutality that makes it stand apart from other games.

6/7 – EXCELLENT.

Games with a touch of brilliance. It might only just miss out on being an absolute favourite, but you should definitely play this.